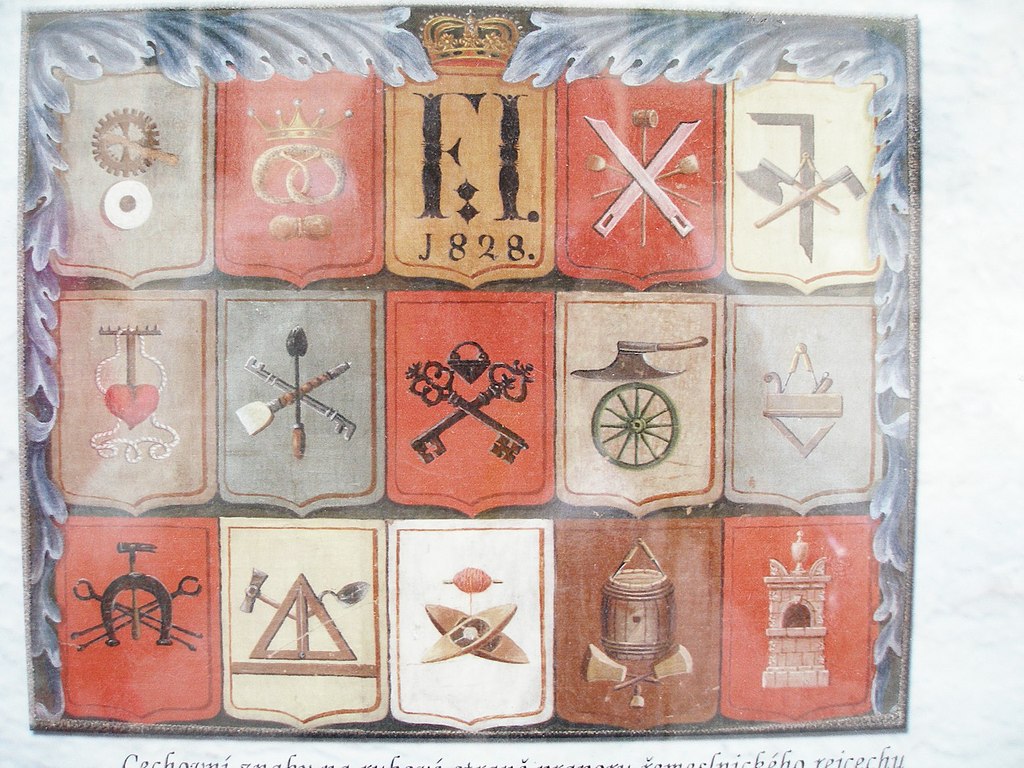

Remember in the olden days when groups of crafts people or business people would form guilds for mutual support, safeguarding their way of life, and keeping an eye on what other people in the business were doing?

Actually, we still do that. Most countries, for example, still have a bread baker’s guild. Then there are trade unions which perform a similar role of organizing and trying to ensure fair wages, and for writers there are professional organizations, or writer’s societies.

There’s a professional writing organization that has been formed around each genre of writing currently commercially viable. I myself am a member of several writer’s groups.

Sisters in Crime, (particularly but not exclusively for women) writers of mystery/crime.

I’ve also joined The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, which includes writers of board and picture books, middle grade, and young adult.

If you write romance, then you’ll want to join the Romance Writers of…(America where I am, but other countries may have their own version.)

Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association has this nifty logo:

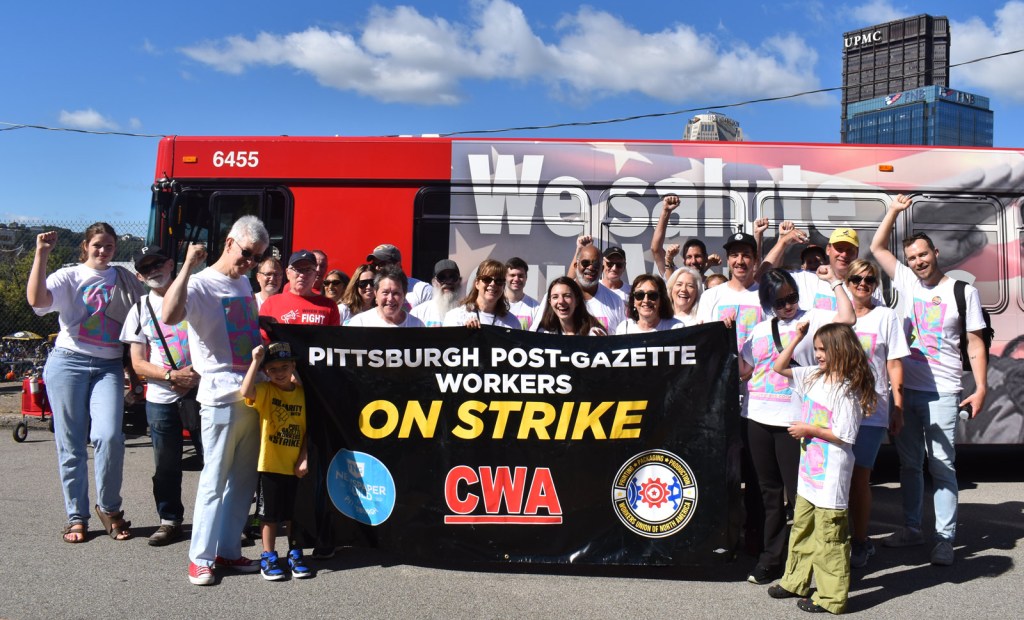

There’s also the Writers Guild of America East, and West, which represent screen writers and is still known collectively as The Writer’s Guild.

Technical writers have their own associations, which vary by the nation you live in, and sometimes by industry.

Why Join a Writing Association?

Aside from the comradery and opportunity to talk with people working in the same genre/industry you’re working in there are a number of very practical reasons to belong:

Educational opportunities including conferences and workshops

Funding for writing fellowships

Ability to enter association run contests for writing

Access to legal consult

Access to standard contracts

Support if you’re in a context of being sued or suing

More immediate knowledge of class action lawsuits around writing that might impact you

I think we’re all being reminded more often that we cannot take for granted that others will respect our work or pay us a fair wage for it. This isn’t a new problem and is at least in part why guilds go back for hundreds of years.

Whether people are taking our work to feed their AI or trying to get our money by convincing us they’re going to provide a service that isn’t real, the more we talk to each other and share information, the more we protect ourselves.

Stay strong, stay connected.