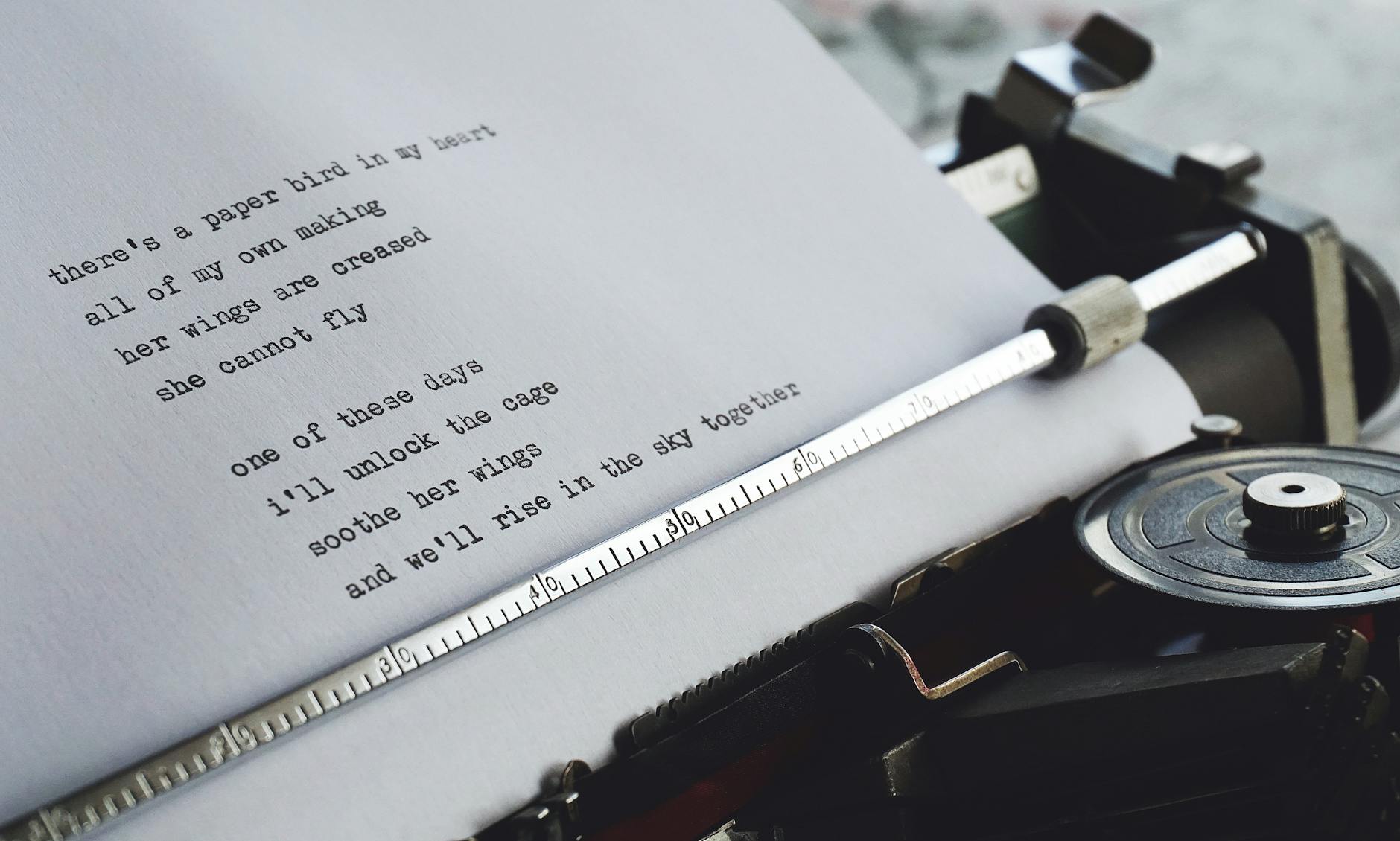

I’m old enough to remember a time when manuscripts were actually typed out on electronic typewriters. It took a week or more for one’s mailed manuscript to reach the physical ‘slush pile’ of an editor or agent, where it would wait for months to be read. Statistically, the thing most likely to happen next – if one had included a SASE (self addressed stamped envelope) would be a rejection letter, that spent a week or more making it’s way back to the writer.

It was a right of passage back then to attach the rejection letters to one’s walls, until one could basically paper a room with the palpable lack-of-want one’s writing was experiencing. So many of we creative types are already prone to self-doubt, morose thought patterns and moods, it is little wonder that so many have ended up self-medicating.

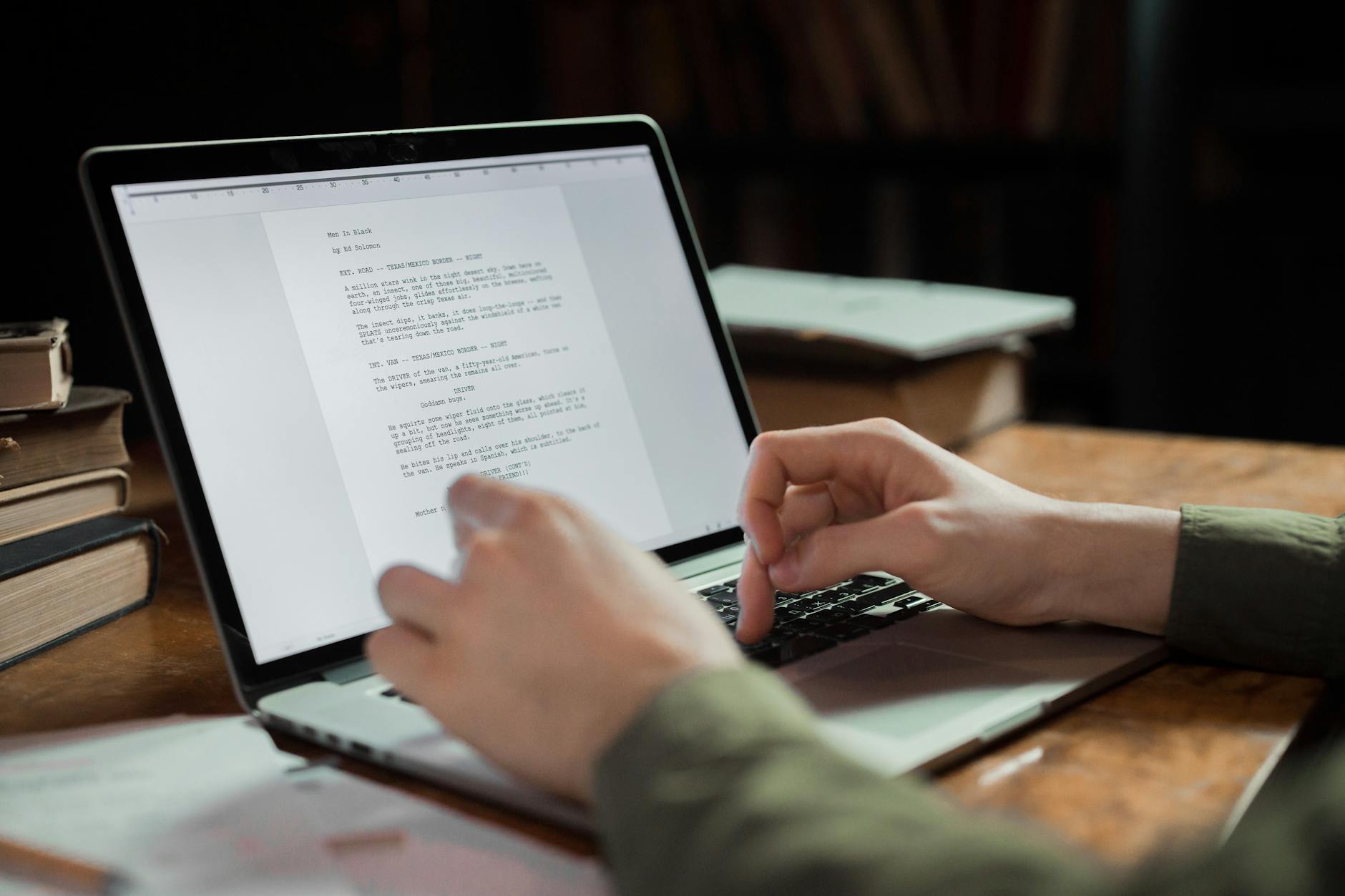

These days submitting is done online. Electronic files sent often through a platform like QueryTracker, where one answers questions about their genre, word count, comparable books, publishing history, biography, and tag line. Technically, this makes the still statistically likely rejection quicker. Recently I submitted and received a polite, ‘hell no’ within the same week. That’s impressive.

Here’s the funny thing about this process. We, as writers, know that the polite decline of our work is the most likely outcome of every interaction where we submit. We know it’s coming and yet, each rejection still feels a little bit like a soft sting. One more person who takes a quick pass on the manuscript you have labored over.

It’s all logical of course. Agents and editors are overworked, have limited resources, and can only take on projects they can passionately defend and promote. They also have to be able to reasonably expect sales of the final product. On their end they are looking for that needle in a haystack: the work that really excites them, and has a potential market, and has a high enough potential for sales to make everything invested in getting that product to market worth everyone’s time and effort. If they don’t love the work and immediately have an idea of how to market it, it has to be a no.

Note: this is a multi- part consideration. 1) do I love it, 2) how can I sell it, 3) can I sell enough of it to make my company a profit (has something too similar already been published) ?

Writers tend to focus on the first part of that when we’re rejected; omg, they didn’t love it. But it’s just as possible that they don’t readily see a way to market your work, or that they’re already marketing something similar, or that while they think the finished book might sell, they aren’t sure it will sell enough to make it profitable.

If one takes the time to submit their work to an agent or publisher, one is hoping for publication. Reaching that point though, can be a really long, hard road. Perseverance is key. Remember, the difference between most unpublished and published authors is that the published author sent out another submission after their last rejection.

Perhaps one day we’ll talk about when to consider that rejection may be trying to tell you something about a need for revision of either your submission package or the manuscript itself.